Simply Beautiful

Mountains, peaks, and summits.

Beauty in rawness.

Perfection in simplicity.

I arrive, out of breath, at Téryho Hut in the Tatras and answer the call with an annoyed, “What now?!”

“It’s Mára Holeček,” comes the voice on the other end.

“Oh, sorry, Mára, go ahead,” I say.

“Want to join me on an expedition to the Himalayas?”

“Yes, I’m in!”

“But you don’t even know where…”

“I’m just in that kind of period of life…”

SURA PEAK

Khumbu Himalayas

6,764

m a. s. l.

M6, avg. ∡ 70° (max. 90°), 1 500 m

first ascent in alpine style

The expedition to the Himalayan peak Sura Peak 6,764 m a. s. l. by Marek Holeček with Matěj Bernát went down in the history of mountaineering. On May 23, 2023, they climbed the west face together and named the route Simply Beautiful.

The Explorersweb.com portal ranks the first ascent among the TOP 10 expeditions of 2023 and it was also awarded as the Czech Republic's Ascent of the Year. It took the climbers three days, during which they bivouaced in extreme conditions of exhaustion in a tent suspended directly in the ice face and with almost no food.

An original and award winning film titled Simply Beautiful was created about the expedition, which was created in collaboration with the leading Czech outdoor film director Tomáš Galásek. You can find it at the end of the article .

The only certainty is the knowledge of uncertainty

Milan Kundera

Then, on April 27, I meet Mára at the Prague airport. It’s my first time meeting him in person—until now, I’d only known him from TV and stories.

The week before departure is the usual scramble to answer one burning question: What’s the minimum amount of sleep I can get over a seven-day stretch? I find my answer in the number four—an average of four hours of sleep a night over the past week.

I fall asleep before takeoff and teleport straight to Dubai. A quick layover, and by 4 PM local time, we’re leaving Kathmandu Airport, greeted by the city’s distinct, sweet scent—a mix of smog, incense, and dust. If someone blindfolded me and dropped me here, I’d recognize the smell immediately.

Four days in Kathmandu. Unpacking and repacking, and the essential stops (read: "Czech Pub"). By day four, we’re fully marinated in Kathmandu’s smell and more than stuffed with Trav’s fried cheese. At 1 AM, we load into a car headed for the airport and take off for the mountains. The plane is twice my age, and I’m sitting on seats made of onion sacks.

We made it! The onions and us land safely in Lukla. Our journey toward the dream of a first ascent in the Himalayas begins with a detour for acclimatization—an eleven-day trek over five-thousand-meter passes, lodge to lodge.

Occasionally, I get lost in the mist and find myself on an unfamiliar peak. The altimeter shows an elevation over six thousand meters. I don’t know the names; maybe the altimeter’s just dazed from the Himalayas and the daily hours-long walks between primitive homes of local Nepalese.

Walking, sleeping, a bit of food. The simplicity of basic needs. The absolute contrast to the average demands of Western civilization. Often, I’m alone with my thoughts for hours.

After eleven days of trekking, we finally say goodbye to the last comforts of modern civilization. Farewell to roofs, warmth, and electricity. And to our one link to the world—a satellite phone—we say hello.

Unfortunately, I also say goodbye to my health, though luckily, only my physical health. My body decides to round off my body temperature to 40°C, my head feels double its normal size, and my legs feel three times as heavy. And to top it off, I’m experiencing the symptoms of the worst male disease—a cold.

Now, I’m questioning the decision to send the porter ahead a day with Mára, confident we’d catch up with him en route to base camp. After the hundredth time collapsing while crossing the Amphu Laptsa pass, gasping for air, and needing a hundred breaths to clear the darkness from my vision, I’m becoming certain it was a mistake.

On the hundred-and-first time I pick myself up, I’m finally at the pass. I’m stitched up like a quilt, honestly considering a bivy spot. Below the pass, I see the crumbling walls of an abandoned shelter. Back home, I can run 100 km in half a day; here, I’m not sure if I’ll make it there by nightfall. I’m totally done…

I’m thrilled to see Mára and Hoďas waiting for me. They set up my tent, and I crawl inside.

Fourteen hours of delirium follow, but I wake up with no improvement. Climbing on the wall is out of the question—all my energy is focused on “conquering” base camp.

The next five days pass in the same rhythm. Chills, heatwaves, chills, heatwaves, sometimes hallucinations. I’m chasing imaginary mice around the Salewa logo on the tent ceiling. When I’m not hunting mice, I’m imagining the helicopter that’ll take me back to civilization in the morning. But each morning, I decide to tough it out one more day. I can’t leave Mára here! I keep pushing, day by day, until things finally turn around. Chewed up like gum, my thoughts of pushing upward slowly start to return.

So far, we haven’t really achieved anything here, and I’m already physically wiped out.

We put in a weather request through Alenka. The message, “Don’t wait—go!” is clear enough. Time to pack our bags! Some things are harder to pack, like food, especially when preparing for an unknown number of days in unfamiliar terrain. But the forecast seems promising.

We trudge toward the wall in a snowstorm.

The weather order hasn’t quite been delivered.

We set up the tent at the base of the northwest face. This isn’t going to be like a casual hike to Kokořín. My position by the tent’s entrance has a clear purpose: head chef for the expedition. Thankfully, the world of alpinism is ruled by instant meals. I drift off to sleep, dreaming we’ll reach the rock barrier tomorrow—but, as I later find out, that’s just a dream.

At 6:30 a.m., I pull the tent’s zipper open, frost falls from the walls straight onto my face. I start up the stove, a liter of lukewarm water and a bar—our morning ritual begins. The process from waking up to taking the first steps is a long ordeal. Everything takes time; everything leaves you breathless, and we’re still on flat ground.

We cross the bergschrund, the starting line for big wall climbs. We climb together, using the full length of the rope, occasionally securing with an ice screw or two. The rhythm of crampons and ice axes breaking the silence is interrupted only by gasps for air.

My legs grow heavy, darkness edges into my vision, and my head drops between the ice axes. Hypoxia.

After a few hours, we encounter the first vertical ice steps, and it becomes clear that reaching the rock barrier today is out of the question. What remains unclear, however, is where we’ll sleep.

(A side thought: given where we are on the wall, my calves are already pretty much trashed.)

Then, Mára calls out from a hollow in one of the ice ribs draping the lower part of the wall like a veil. A break in the otherwise unyielding ice—a mini cave, a crevasse. In the Alps, I’d steer clear of something like this, but here, it brings a surge of joy. We’re still far from the rock barrier, but having a flat spot to sleep on is a luxury.

Melting snow for water and managing dehydration and caloric deficit with instant meals become the focus of this stationary stage of the ascent.

The sun isn’t shining the next morning, which is almost guaranteed in the spring Himalaya season, yet today, it’s not. Light snow showers keep us waiting, pushing our start time back.

Finally, a little after nine, we head off into fresh adventures, once again into the absolute unknown. We keep up the rhythm of ice axe and crampon work. The slope angle is around 70 degrees, and as we near the rock barrier around noon, it’s clear that it looms even steeper above us. I’m glad Mára is the brains of this expedition, though I can’t help but wonder how we’ll save our skins from here.

Overcast skies and snow take the last bits of positivity, and we start a grueling fight through mixed terrain, where the rock holds by sheer willpower. The route decision comes easily: straight up. No rocket science.

Simply Beautiful movie

Rok výroby / Year of Production: 2024

Stopáž / Runtime: 27:29 min

Scénář / Written by: Tomáš Galásek

Kamera / Director of Photography: Marek Holeček, Matěj Bernát, Tomáš Galásek

Střih / Edited by: Tomáš Galásek, Lukáš Šereš

Zvuk / Sound Design: Jiří Hloušek

Účinkují / Cast: Marek Holeček, Matěj Bernát

Produkce / Production: Marek Holeček, Tomáš Galásek

Režie / Directed by: Tomáš Galásek

The weather continues to develop… and not in a good way!

It starts snowing heavily, the wind picks up, and small powder avalanches are coming down from the cliffs above. There’s no way we’ll make it past the rock barrier into the final ice pitches. We need to find a place to endure the night. We have options—bad or very bad. The wind intensifies, making it clear we need to anchor ourselves somewhere. We’re left with no choice but to go with the very bad option. Hanging from our belay, we start hacking at the ice with our axes to carve out a ledge. After 20 minutes of chopping, we have a level area of about five centimeters—and then hit rock. We move lower, dig down 10 centimeters, and hit rock again. We’re in deep trouble. After two hours, we manage to carve out a horizontal space roughly 20 by 100 centimeters.

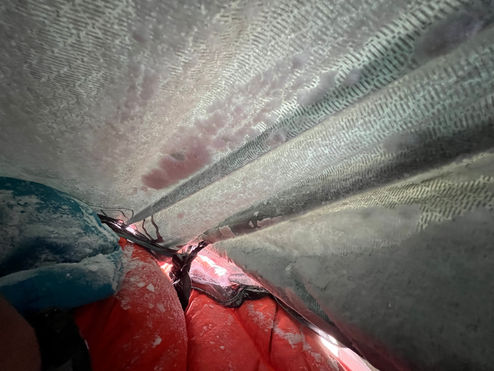

We hang the tent and ourselves on the belay. With our heads leaning against each other, we try to settle in. We might be here for several days. The tent tarp is so close to my head I have to tilt it sideways; luckily, the neck cramp fades after three hours.

The first powder avalanche solves my seating problem by dumping a bagful of snow down my back, erasing the “bench” I had been sitting on.

Heads close together, we breathe through a small opening in the tarp when there’s no snow powder blowing in. At those times, it’s better not to breathe.

Since morning, we’ve only had half a liter of fluids each. We’d both love a drink, but it all depends on the wind settling so we can melt snow in the morning. Nothing is certain here.

The tent tarp is coated with a centimeter of frost and stretched tight over my sleeping bag, pushing out the insulating air. I’m left with the certainty that my feet won’t be warm.

Then comes sixteen endless hours. Sixteen hours of being unable to move, drink, or breathe deeply. Just managing your mind and your own head.

I’ll never forget the moment around 3 a.m. when the weather calms for a moment. Unzipping the door of our hanging tent, I glimpse the peaks of the Himalayas under a starry sky from somewhere suspended in the wall.

In the morning, the weather finally eases up. I melt snow, and the first sips of water peel my tongue from the roof of my mouth. Everything is wet, and it’s freezing outside—minus 20 °C or lower. Packing up our garbage bag–like tent shelter, where we spent the night, and getting ready to move takes over two hours.

Traversing below the critical pitches, getting the body moving feels like torture. I managed between zero and thirty minutes of sleep.

Now, onto those key pitches. Mára leads, and I practically push him upwards with my gaze. He’s the more technical climber, while I’m carrying a bit more gear in my pack. At his call of “belay,” I climb as quickly as possible to ensure we don’t have to spend another night hanging off the side of the mountain. Mára pulls off incredible moves in this rockfall zone. When the pitches get easier, I take the lead. Beyond the rock barrier, we reach a ridge covered in hard ice. The weather is heading where it did yesterday…

…into the dumps! The wind is fierce, and here we’re again done like a patchwork quilt — seen that before on this trip. We press on! We need to find a spot by nightfall — not to sleep, but just to survive.

I spot a crevice in the ice wall—a rare stroke of luck here, far from the Alps! I dive in headfirst and pull Mára up while setting up the tent one-handed. I’ve got every layer of clothing on, and the thought of relief in a damp sleeping bag is just a bit hazy. We crawl into the tent and sleeping bags; it takes an hour before our bodies warm up enough to melt snow for water and food.

Then, we collapse into a coma—well, sleep. We know we need to push past the summit and as far down as possible tomorrow; Alenka says the weather will turn dramatically, and that only means one thing here: worse. That’s all the motivation we need. Good night.

Morning rituals. My body, in a constant tremor from the calorie deficit, finally stands with Mára on the summit after three hours. Five minutes there, and then we’re scrambling down—no feelings of relief, nothing. Just thoughts of a fast, cowardly escape.

We begin our descent. The goal is simple: get as low as possible by the end of the day! For the first few meters, I’m hopeful that the terrain won’t be so tough—“we’ll be down by dinnertime.” But after 100 meters, the reality sets in, shattering that illusion. We face hours of descending a complex ridge, full of cornices and steep ice traverses. We’re roped together but without intermediate anchors between us, offering not even a naive hint of security.

The first hours are spent in constant, cautious retreat, moving backward across icy slopes, fully engaged with all four limbs. Any mistake here comes with the highest price.

We’re fighting, pushing our exhausted bodies to the absolute limit. Alenka’s last weather update tells us today is the final window for descent. The thought of more days stuck in a tent, battling gale-force winds, with soaked gear, little food, and limited gas to melt snow for water, propels us onward.

After hours upon hours, we transition from the snowy ridge to rock. As the last sunlight fades, we push hard to reach the valley floor before darkness makes navigation impossible.

We succeed! But reaching the Teahouse (a primitive shelter, yet to us, it symbolizes sheer luxury in contrast to recent days) still requires hours of walking. Stumbling in a near-delirious state, we navigate scree slopes, guided only by our watches. Only fragments of those final hours remain in my memory.

At 10:00 p.m., I push open the door of the simple stone hut.

There are embraces with Mára, Pavel, and the porters.

Emotions flood in—relief and pure joy.

Warmth, light, water, food, safety. Nothing more is needed for complete happiness.

I have never conquered; I have only been permitted. In life, we learn from our own mistakes or from the experience of others. Thank you, Mára!

And the story of battling winds and snow for two days as I scrambled down the mountain to Lukla to catch my flight—and make it back in time for my patients in the Czech Republic—will have to wait for another time.

The story of the first ascent can be seen in the movie bellow.